What the Do-No-Harm Principle Means for Program Implementation

Using second order of thinking tools to factor the do-no-harm principle of practise in program planning and implementation

PROGRAM MANAGEMENT

Development and humanitarian aid workers emphasized the importance of a recognized set of “principles of practise” in planning and implementing their work. Different idealistic principles are abundant in the literature of different development agencies. The most prevalent among them are neutrality, inclusiveness, human rights, gender and do-no-harm. These principles (and others) are more than statements of intent, they are guiding precepts with operational implications in how we plan and implement our programs. In this article I want to closely examine the do-no-harm principle (DNH) and think how we can practically use it.

Background

What is it?

Lets start with a definition of DNH, here is one of many that covers the relevant elements:

Do no harm is an approach which helps to identify unintended negative or positive impacts of humanitarian and development interventions in settings where there is conflict or risk of conflict. It can be applied during planning, monitoring, and evaluation to ensure that the intervention does not worsen the conflict but rather contributes to improving it. INEE Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies

The definition spells out the principle as a full fledged risk analysis exercise. Development interventions are drivers of change by design. Change triggers a ripple effect of consequences. The planned consequences that planners hope to achieve are positive. However, unintentional negative consequences may also happen. DNH is the thought process that guides program planners to actively think about the negative consequences that may happen and plan to mitigate them or in some cases avoid them completely.

DNH vs. Risk Analysis

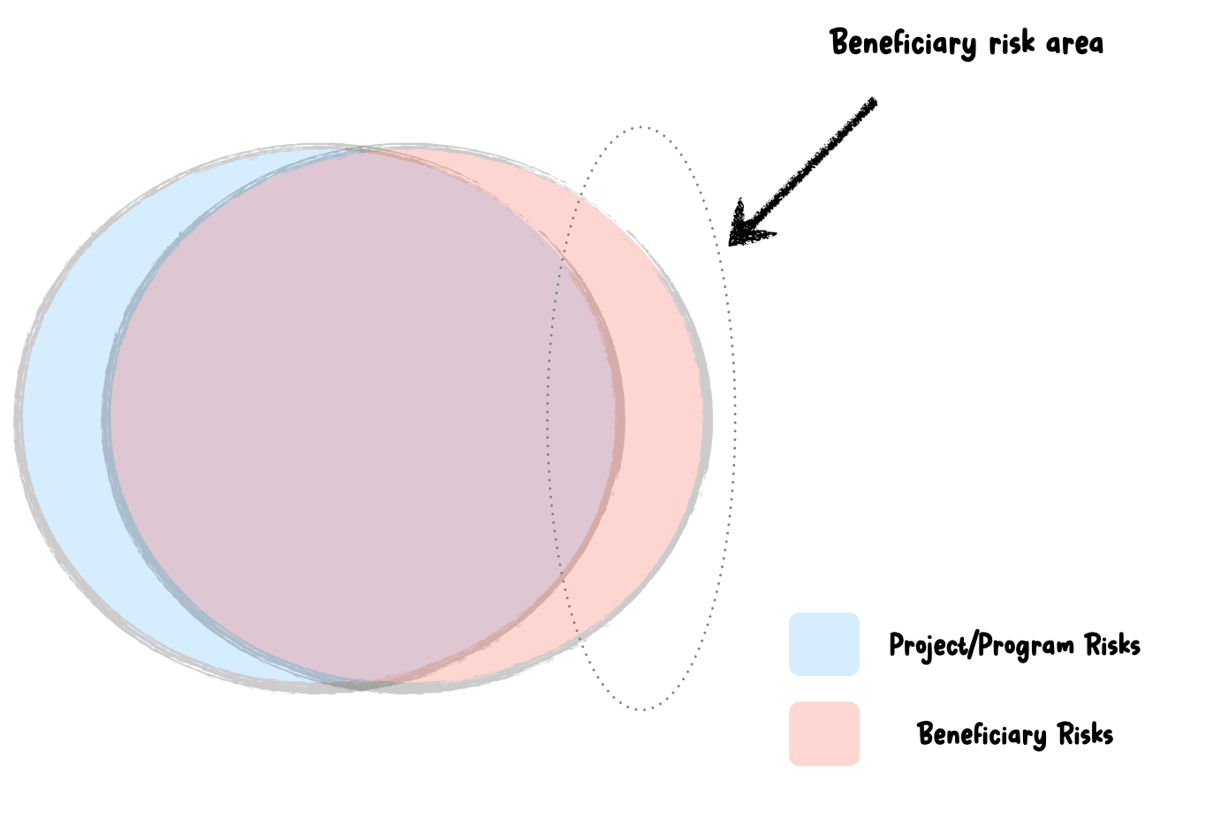

It is important to differentiate DNH from the regular programming risk management. Program risks deal with the risks that affect the program whereas DNH deal with the risks that the beneficiaries/external stakeholders will be subjected to as a result of the programs intervention. Program planners are trained to think inwards about the risks concerning the program (both internal and external risks). DNH is the failsafe mechanism that protects the beneficiaries in the planning. Although both types of risk overlap (program risks and beneficiaries risks), there is an area - the beneficiary risk area - where they don’t overlap and thats the area that needs to be forseen and addressed by the DNH principle.

Example

One example of drastic harm that may happen due to oversight in applying the principle is when an international aid agency working in food security in a remote region in an east African country planned a relief box project that targets low income families in the region. The targeted families were households of subsistence farmers. The idea was to supply each family with a box containing food supplies that should suffice the households for a few months in a season where the agricultural crop in that region failed due to severe drought. The box contained basic food items (flour, sugar, beans, cooking oil). On the face of it, this project sounds like a well-intentioned, well-thought intervention.

On implementing this project, the international agency decided to avoid the logistic complexity of shipping the foodstuffs into the region by purchasing it from the local market. They purchased the needed stocks of food and successfully distributed the food items to the targeted beneficiaries. The project ticked off the proverbial box of this activity and reported the project to the donors as a success.

But, what happened after the project completed its activities was far from a success. The decision to purchase the items from the local market caused a major increase in the demand side of the market spiking the prices beyond the means of members of the community from outside the targeted group (civil servants, technicians and manual labourers). This in turn caused turmoil in the region in addition to open animosity towards the targeted group (the subsistence farmers) and all the international aid agencies in the area.

It's safe to assume that the aid agency would not have purchased locally and set this unfortunate chain of events intentionally. Their mind was probably focused on getting the needed supplies to the families as fast as possible. They probably thought about the lead time it would take to import, transport, prepare and distribute the relief boxes and decided to cut it by just buying locally. This could have been avoided had they weighed the possible implications once they considered the local purchase decision.

Practical Application

DNH, and its factoring into each decision point is the only way to avoid such scenarios. DNH implies that we ask ourselves important questions when planning and implementing:

what are the immediate, short term and long-term consequences of our actions?

do the consequences put someone at risk or increase their vulnerability (vulnerability includes safety, discrimination, livelihood, and access to services)?

In answering these questions, and thinking about the first, second, and third order of consequence we can think more clearly about what our decisions mean, and more critically what each decision may lead to.

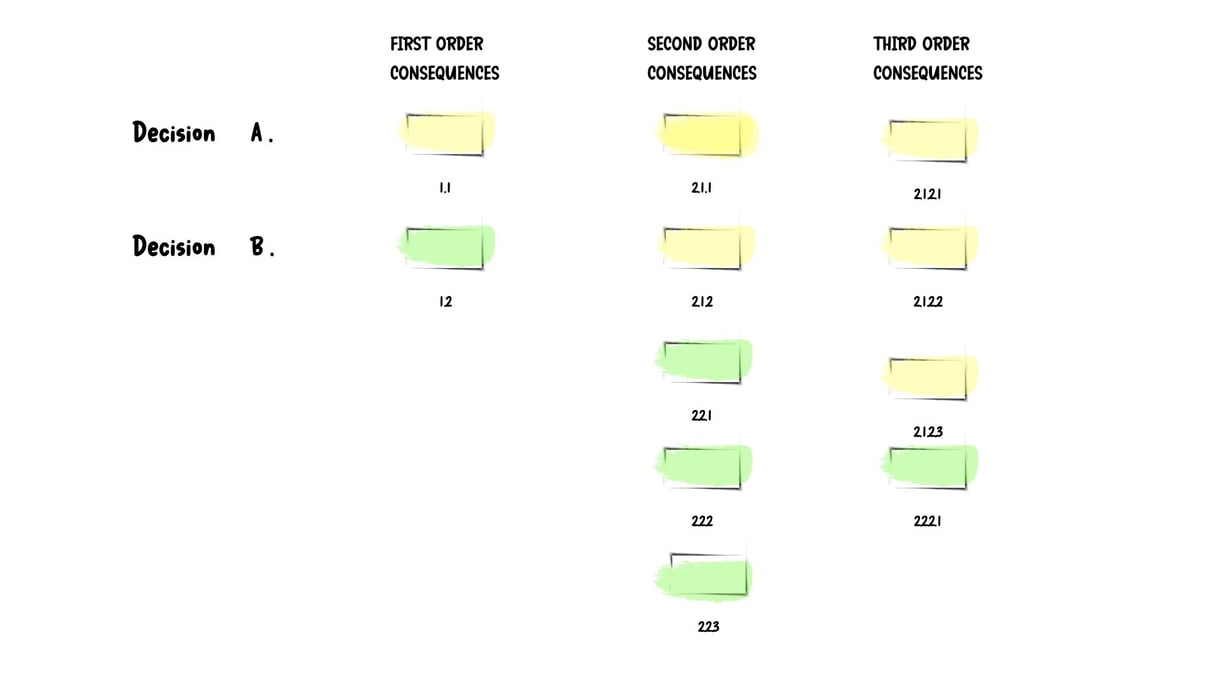

Imagine a corkboard where two decisions (A and B) are weighed and examined. Each order of consequence is assigned a column (an order of consequence is the effect of a decision, the first being the immediate effect, the second being the following effect, and so forth). Careful reflection on plotting consequences in this board would probably have gone as follows —>

Decision A: purchase the foodstuffs from the local market.

First Order Consequence 1.1 : food materials are quickly supplied for distribution.

next, we move to the second order of consequence, i.e. what will happen after 1.1.

Second Order of Consequence 2.1.1: market prices sharply increase;

Second Order of Consequence 2.1.2: community members from outside the targeted beneficiaries become unable to purchase essential foodstuffs;

here we established the negative consequence, we may stop here but it is advisable to keep going so as to safely cross out the local purchase decision.

Third order of consequence 2.1.2.1: malnutrition proliferates in the community among the non-targeted beneficiaries;

Third order of consequence 2.1.2.2: the targeted beneficiaries encounter aggression from the non-targeted beneficiaries;

Third order of consequence 2.1.2.3: the community in the region becomes suspicious and openly belligerent towards international aid agencies.

You may test this method with this example and apply it to Decision B, which is going through the prolonged process of importing food from abroad. On examining the well-thought consequences of all the decisions on the table a well-informed choice may be made. The columns above are one simple tool that can be used, a reversed decision tree may also serve the same purpose. The template is important but what is critical is the clarity of thought, presence of mind, and in some cases, the imagination to envision what well-intentioned decisions may lead to.